...WHICH IS TRANSCENDENTAL…

Stage 18 / Thursday 14 May / From Estaing to Conques / 35 km

It is difficult to leave Estaing, one of the most beautiful villages in France, with its ancient bridge and its castle which give it a medieval touch, but I must climb the causse [calcareous table land] of Sébrazac and other hills today in a long stage which will bring me to another gem nestled in its moors: the abbey of Conques. I leave early in the morning, and work up to a good rhythm above the misty valley of the Lot river, and in gaining the heights, I feel transcended!

What is this transcendence that illuminates here and there the mists of my existence with a sudden momentary glow? As here the rising sun which dissipates the fog of the valley … But the transcendence manifests itself not only in the exceptional panoramic view; it can also be the tears brought on by Handel’s Alleluia when the entire audience joins in the chorus; or the “Ah ha!” that escapes on making a sudden discovery. A poem perhaps, nicely crafted, and whose meaning and words resonate as well as the melody. I murmur, “Town, tower, shore, deep where lower cliff's steep; waves gray where play winds gay, all sleep! Hark! a sound, far and slight, breathes around on the night …” (The Djinns, Victor Hugo) [Murs, ville, et port, asile de mort, mer grise ou brise la brise, tout dort ! Dans la plaine naît un bruit, c’est l’haleine de la nuit …]

From this entire physical scene that I contemplate, there indeed emanates something like an unreal breath, a symphonic reflection of a transcendental presence softly blowing. Can I rationally discern the limits of this breath that seems to come from elsewhere, and which brings me to such a degree of peace and serenity? This sensation of calmness comes to me also when justice is done, or when morale is saved, and also when I reach the sacred through an encounter filled with profound and valorizing purity: the smile of a child, a Gregorian chant, etc.

A time of transcendence often seems to imply the vision of a person, the meeting of another person, even if this other person is sometimes only the perception of my own image, seen and valorized by another. It is more a relation of communion than of knowing. Not a knowledge that would oppose ying and yang, a spiritual “front” opposed to a material “back”, an “inside” to an “outside,” but rather a communion which would give to this material the beginning of a spiritual reality. Like the young child, not yet corrupted by the things of life, and who smiles at me: he sends back to me the image of someone in whom he can have confidence, he lets me know and transcends me with purification.

In the same way, arriving beneath the high naves of the abbey church of Conques, the disconcerting purity of the Praemonstratensian monks’ voices singing a troparion (a short antiphon) sweeps away my cramps and washes off my worries: how and why is this of a transcendental nature, this chant by a few consecrated men?

Is there an explanation for transcendence, or does it on the contrary encase that which goes beyond reason? Isn’t this adjective just a profane synonym of the word “mystery”, whose connotation is more religious? Lacking an explanation before a phenomenon which touches and moves us, we evoke the word “transcendence” when our ancestors said “mystery!” And as a result, is all this questioning founded? When I imagine a transcendent God, am I implicitly only admitting that I don’t know what I’m talking about?

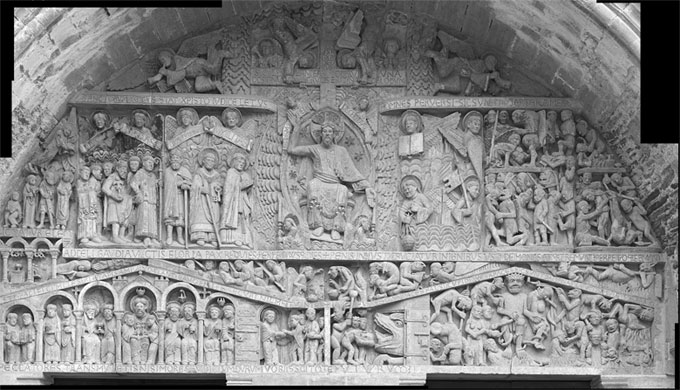

I leave the church and its enchanting melodies, and outside in silence I begin to contemplate the scene of the Last Judgment, which dominates the entrance tympanum. There I quickly fall back into the concrete: certain artists of the Middle Ages did not seek to make things either too mysterious, nor too transcendental!

In the center, the piercing and enigmatic glance of a majestic Christ, both king and judge. On one side: the good people are rising, welcomed into eternal bliss by their advocates, the saints, apostles, and angels. On the other side: the temporary dwelling place of purgatory. Sinners there are hoping for their atonement [the forgiveness of their sins]. At the bottom suffer the worst evil-doers: all sorts of devils try to push them toward Gehenna (hell). But Satan the accuser forces a laugh out of spite. For the final victory of Christ can still save all: through Him, with Him and in Him, there is a clear invitation … less to transcendence … than to the final ascension and immortality with Him!

Tympanum of the Church abbey of Conques – by Pierre Séguret